Sunset on Korcula. 20 x 30 cm, oil on panel.

I’ve been painting the fleeting light of Southern Croatia for the last couple of weeks and thinking a lot about painting into, and out of, effects.

Landscape paintings usually depict one moment or effect of light. When painting outside, light effects change the whole time the artist is working. Part of the responsibility of the artist is to decide which of the various positions of the sun and shadows will be in the final image. Furthermore, when it’s the painter’s first time somewhere, it can be difficult to visualize perfectly what will happen with the light over the course of a multi-hour plein air painting session.

For the last few years, the light effect that has most interested me is the high sun at midday. My subjects are also often north-facing, and thus back-lit. It’s usually an easy route to take for plein air painting. The number of hues is greatly reduced and the values and shapes become more important. Though it would seem the opposite, I find it easier to get an effect of sunlight or heat, than working with the sun behind me. Most of my favorite historic plein air works are back-lit (it’s hard to think of a good Corot, for example, that isn’t). Also, the light changes very slowly in the midday hours. I’ve worked for up to six hours straight on a midday painting where the shadows and overall effect didn’t change a great deal.

When I first started painting outdoors, however, I really loved the late evening light. Charles Cecil taught me much of what I know about landscape painting, and his own favorite subject is the orange light of the Tuscan evenings, or ‘Golden Hour’. The problem with late light is that the effect lasts only a few minutes. In order to paint a sunset or sunrise painting, you either have to work for only 15 minutes a day, or paint into the effect. Painting into the effect simply means as the afternoon light turns to the golden evening light, the effect will become more and more what you’re after. (Presuming, of course, that the evening light is the desired effect. If the afternoon light is your subject then you’re painting out of the effect).

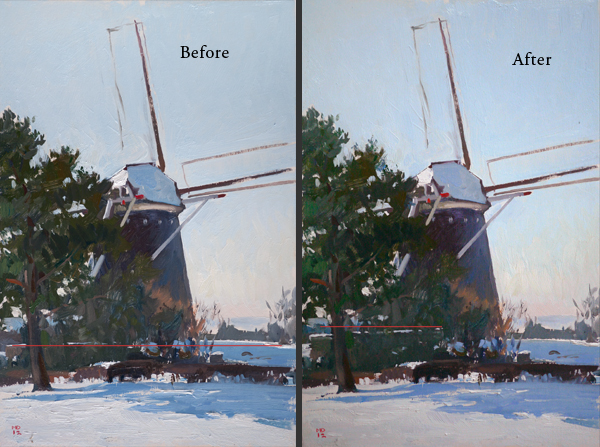

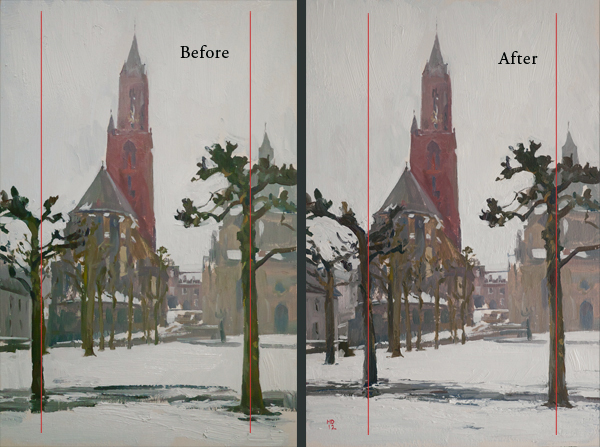

The trick to painting into an effect is to work on the drawing until the desired effect is present, and then change the colors and shadow shapes at the end. For painting out of the effect the opposite is true. You start with color notes and the shadow shapes, and then polish the drawing as everything changes.

In the sketch of Korcula at sunset above, you can see the blue around the palm tree from when I did all the drawing with the afternoon light. I then changed the whole color scheme when the sun set. I’ll later polish things up in the studio when the paint dries.

Understanding the mechanics of changing light and how to deal with it is an important part of plein air painting.