Last winter, around the time that plein air landscape painters migrate back into their studios to begin enlarging sketches into larger finished pieces for the coming year’s exhibitions, I was thinking a lot about this painting entitled Lake, Rus by Isaac Levitan.

Isaac Levitan. Lake, Rus (1900).

It’s a large landscape and, like many larger paintings, the artist made a number of small preparatory drawings and oil sketches for the final piece. The studies I have seen for this piece have a wonderful freshness to them and a great sense of light, place, and the eternal captured in a moment.

What I find most interesting about Lake, Rus though is that the place doesn’t exist. None of these studies, nor the final piece, were done from life. There was no proportional comparison, no sight-size, no photo reference, and no camera obscura used in the making of the painting. It’s a very different method of picture making than my own, or that of many painters I know.

Artists often disagree about the techniques and materials used by historic painters. In what’s referred to as confirmation bias, their beliefs regarding the working methods of these long-dead artists often conveniently coincide with their own preferred painting system. For example, some artists who use photographs (or who can’t draw well without them) believe the great historic painters all used photography or another optical device like a camera lucida or obscura. Artists who use sight-size have found (some say inconclusive) evidence to prove that sight-size was a common portraiture technique dating back to the Italian Renaissance. Painters who use a grisaille technique are convinced the same method was used for some of the best oil paintings in the Western Canon (this is probably true), and so on.

In the past couple of decades there has been a lot of media attention around the idea that the Old Masters couldn’t draw or paint without the use of some sort of optical aid, be it a camera lucida, camera obscura or some other mirror/lens combination. Much of this started with David Hockney’s book Secret Knowledge and his subsequent media crusade. I read the book and saw him give a talk in Florence. Like the camera-obscura proponents before him, he has little evidence to support his assertions and his sentences in the book often start with some variation of “I think…” or “It seems to me…”. Overall, it’s an amazingly unscientific book, though the reproductions are beautiful. Other writers have disproved his thesis already, so I won’t go much into it. That said, I would like to reiterate that during the 20th century, despite the plethora of technological advances, the best realist painters have continuously avoided using any optical aids. In portraiture, where an accurate likeness is of the utmost importance, every account describes great artists like Sargent, Zorn, DeLaszlo, and Annigoni working directly from life for important commissions, even if they were known to use photographs for less important work. If photography or optical aids were so useful, why wouldn’t these artists use them for their most stressful and prestigious projects? Today, if we look at the best contemporary naturalistic painters, artists like Antonio Lopez Garcia, Richard Maury, Joseph McGurl or Jacob Collins, all of whom are able to produce excellent naturalistic images with accurate shapes and ‘photographic’ value ranges, these are the very same painters who eschew or minimize the use of photographs, projections, or other technological devices in their work.

Unfortunately, despite the fact that almost every art historian, realist painter, and visual scientist has rejected Hockney’s theory, there was a media frenzy to promote it and many people have accepted it as truth.

A couple of years back there was a documentary made called Tim’s Vermeer and the genesis of the story came from Hockney’s debunked book. The premise of the film is a rather extreme version of confirmation bias and it tells the story of Tim Jenison, a self-described computer graphics guy with no artistic training, who “uses technology to make realistic, beautiful images” as he sets out to prove that Vermeer also had no artistic training and used technology to make realistic, beautiful images.

I saw the movie a while ago and I remember thinking it must be a hoax. It was made by the magicians Penn and Teller, who used to have a cable tv show called ‘Bullshit!’. In this show, the magicians would take pseudoscience, paranormal beliefs and common misconceptions and subject them to critical thought and concrete evidence in order to show that these ideas are false. My thinking was ‘why would they then make a documentary which is patently bullshit too?’ It made no sense. I thought that after a couple of years they would come out and admit it was all a joke to show how ridiculously easy it is to sway public opinion to believe anything via mass media. Unfortunately, that appears to not be the case.

People have asked me what I thought of the movie so I figured I’d write about it. The TLDR is that I didn’t like the movie because much of what they claim is either outright false or, at best, misconstrues what we know about Vermeer and historic painting methods.

Early on, the movie makes the statement that Vermeer’s painting are special as there are none of the ‘usual artist’s sketches’ under his paintings (they state “he was some unfathomable genius who could just walk up to his canvas and magically paint with light”). That is not necessarily true. First, there are lots of paints, chalks and charcoals he could have used for his underdrawing which wouldn’t show up in the infrared technology they use to look under layers of oil paint. Only marks made by dark media are revealed by infrared images. Vermeer’s own work entitled The Art of Painting shows an artist painting on a grey-toned ground with the underdrawing done in white chalk which, for example, wouldn’t show up in infrared imagining. Both Vermeer and his wife went through great pains to keep this painting in their collection, which has led art historians to believe it might be a self-portrait. Second, it hasn’t always been usual artist’s practice to do an underdrawing since the egg-tempera days (Velasquez, late Titian, Caravaggio and many of the great 19th-century painters come to mind). And third, we know from studying his paintings that Vermeer’s technique was not just ‘painting with light’ and, like that of many painters in 17th-Century Holland, required lots of glazes over a tonal underpainting. Such a method completely removes any possibility of working a passage in one shot as Jenison does.

To nitpick with smaller examples: They make the claim that a blurred line on the profile of the girl’s back in Woman in Blue Reading a Letter is a chromatic aberration that could only come from a lens. But if it was a defect in the lens he used, why wouldn’t it appear in other paintings? The truth is that anytime an artist wants a form to turn away from the viewer they blur the line. In Vermeer’s painting, if you imagine a razor sharp edge you can see how it would jar the eye. You don’t even have to imagine, just look at Jenison’s final painting. It is quite poor precisely because he makes no attempt to vary his edges. Every edge he paints is sharp as he is shown focusing on each edge at a time in a piecemeal fashion, without any relation to the whole image. This is not the way the human eye sees and clearly not the way Vermeer painted.

The glow that they find so magical (“like an image on a movie-screen”) is probably a resin-based, maybe amber-based medium, and lots of artists from the 17th-century get the same effect in their work. In fact, when you walk through the Louvre, as you leave the late 18th-century Rococo rooms with the Greuzes and Le Bruns and move into the first Neoclassical room with the Davids, it’s interesting to see the switch from those earlier rich and unctuous mediums to the more simple and dryer-looking linseed-oil based mediums that have remained common up to today.

At another point in the movie they state that it is impossible for artists to see subtle value shifts across a wall in relation to the whole image. The filmmakers show an animation demonstrating that people can easily see value differences when two squares are close together, but that it becomes more difficult to discern the difference when the squares are further apart. Like so:

The film claims that Vermeer could only see these value differences if he was some sort of savant, or he had a special super-human retina, or he used their lens. They call it ‘absolute brightness’ (like musicians have perfect pitch) and claim only a lens would allow a painter to see values properly. This is completely false. Artists squint to see the compressed value range that they can reproduce in paint. You can try it at home. In the second image of the squares above, squinting way down will allow you to see the difference in values almost as clearly as when they are next to each other. The human eye can only see a few hundred value changes at a time, so to get the number of values to a smaller range, where subtle differences are visible, artists squint. They’ve been doing so for centuries, and have written about it in treatises. It seems silly that the filmmakers don’t mention this. There are excellent realist painters working all around the world today, getting ‘photographic’ values in their paintings by reducing the amount of light hitting their retinas by squinting. It’s one of the first things painting students are taught.

Vermeer also painted outside. How would he paint changing light effects and moving subjects, such as the clouds in his ‘View of Delft’, by copying from a mirror?

The movie takes a lot of cheap shots at art historians, and no art historian appears in the film. It’s a bit like climate-change deniers made a documentary denying global climate change and couldn’t get any scientists to appear in the movie. The art historical evidence is inconvenient for them. After Vermeer died, an inventory was taken of his possessions and he didn’t own a camera obscura or lens, or any other optical device. This document is still in the Delft city archives and it describes the other objects in his studio. It’s not mentioned in Tim’s Vermeer. They also claim that historic artists were ‘sworn to secrecy’ and never shared or wrote about their techniques. Again this is false. There are a great many treatises on painting techniques and materials written throughout the history of Western Art and none recommend the use of optical devices in painting. Both Hockney and Tim’s Vermeer continually make the point that their theories are not an attempt to diminish the genius of the Old Masters, but their suggestion that these painters were hiding their methods contradicts that. If using an optical device didn’t make painting easier, why would painters hide it? To me this suggestion of deviousness and connivance on the part of historical artists says more about the characters of David Hockney, Penn and Teller, and Tim Jenison than any of the Old Masters.

Sir Joshua Reynolds, for example, did own a camera obscura. This fact is regularly trotted out by the pro-optical device crowd as proof of artists using gadgets as he had one in his possession when he died and it’s still on display in London. What they miss though is that Joshua Reynolds also wrote a great deal about the making of paintings. These writings are collected in his Discourses. In the book Reynolds discusses all aspects of drawing and painting from the technical to the philosophical, but only mentions the camera obscura once, and he pans it:

“If we suppose a view of nature represented with all

the truth of the camera obscura, and the same scene

represented by a great artist, how little and mean will

the one appear in comparison with the other…”

Leonardo da Vinci is also suggested as an example of an artist who used a camera obscura. On this page in the Atlantic Codex he illustrates the inversion of an image through a pinhole. It’s the small sketch of the candle at the bottom of the page. The rest of the drawings on the page are images of optical phenomena and the functioning of the human eye and I’m not convinced he was suggesting its use in painting. In his own work, there is very little stylistic difference between his early work, his fantastical drawings of invented spaces and characters, and any subject where the use of a camera obscura would have been possible. Furthermore, some of Leonardo’s thoughts on art were compiled by his pupil Francesco Melzi into the Treatise on Painting. In the book, tracing shapes using a piece of glass is described a few times, as well as the practice of observing ones work with a mirror to check shapes, yet there is no mention of the use of a camera obscura.

He does, however, specifically warn his readers not to copy the subject the way Tim Jennison does:

“The painter who draws merely by practice and by eye, without any reason, is like a mirror which copies every thing placed in front of it without being conscious of their existence”.

One can go on through the various artistic treatises, but they are all silent on the use of gadgets. What every text written by a painter does repeat over and over is the importance of learning to draw over the course of years.

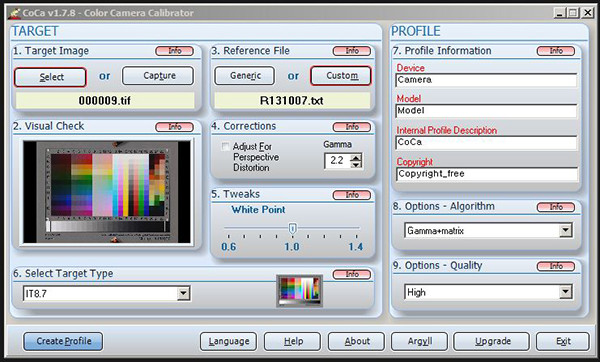

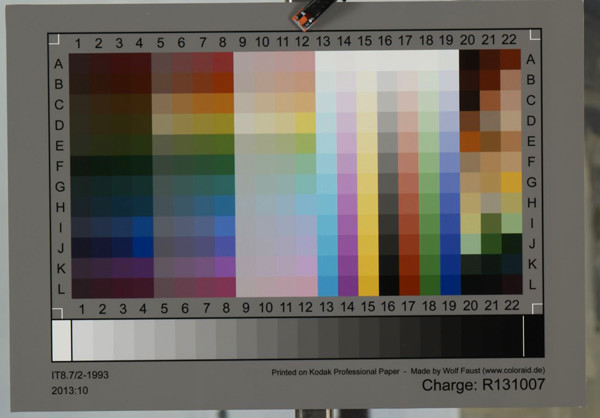

Despite this rant, I am not against the use of technology to make art. I don’t think we should go back to horses for getting to landscape painting spots (though moving slow and being high up is great for scouting), I love looking at the new wave of digital artists I see online, and I will incorporate technology into my own working method to experiment with new ideas. I’ve written before about using video rather than photography for portraiture, experimenting with carbon fiber and Dyneema composites fabric to lighten my plein air painting equipment, and I use weather, map, and sun-tracking apps to plan my outdoor work. I’ve also used Photoshop on occasion to make compositional decisions quickly, rather than doing lots of studies, as seen in the gif below:

Because I use technology sometimes in my work, I am well acquainted with its disadvantages, of which this gif is a good example. My thought here was that since I was able to quickly and precisely move elements around, in theory I would be able to produce a better painting. In reality though there is evidence to suggest that I would be better off doing a number of small studies by hand. Cognitive psychologist Robert Bjorkhe called the principle ‘desirable difficulty’ in his studies on teaching methods, and his discussion of ‘Generation’ is especially relevant. The idea is that generating words, rather than just reading them, helps students remember them better. I believe that artists generating studies also contributes to an understanding of the work that will be different than if the same work is done using technological shortcuts. There is a depth that we get into when spending painstaking amounts of time on an idea that will not be there when using technological shortcuts. It seems commonsense to suggest that doing a number of studies will give an artist more practice and better help them visualize and remember their subject, but we sometimes forget just how much of painting is memory. For a realist painter recreating an image before them, every brushstroke is based on a memory. For Levitan, recreating a whole scene in his head, he would be required to call upon a large vocabulary of objects from memory, and visualize them in a specific light and atmosphere.

I’ve often wondered how our brains have changed over the centuries as we rely less and less on memorization in other areas of our lives. There used to be elaborate systems based on visualizing spaces which were used as memory tools (Frances Yates wrote a great book on the subject called The Art of Memory), and perhaps historic artists were also using these ‘memory palaces’ to store information they might have access to on rare occasions. It would have required years of practicing imagined spaces. Would that have wired their brains differently than ours? For those of us living in a digital age, we don’t really have to remember much at all. We carry the sum total of human knowledge around in a tiny device in our pocket. When you read about the concerns of scholars after the invention of the printing press – that people would lose the art of memorization that was so essential in the days when seeing a manuscript might be a once-in-a-lifetime experience – you have to wonder what they would think about our lives today. We are also bombarded by images in the form of tv and movies, public advertising, newspapers and magazines, and now the internet. Is that going to make us less sensitive to images or more sophisticated with regard to them? Studies show that reading short internet articles and blog posts (!) reduces our attention spans, and I personally notice a difference in my thinking when I stay offline and go back to reading books. How does all of this affect our work? And is relying on technology to make painting easier really producing better artwork?

This is the point that I’m really trying to make here: On the one hand, art is a craft and, like any craft, mastery comes from really hard work. There aren’t any shortcuts. Years of exercise in the form of thoughtful repetition and copying leads to a visual and physical dexterity which allow an artist to create the work of art.

On the other hand, there is an emotional component to great art which comes from the artist’s love for their subject. The subject can be their passion, idea, or just their reaction to the beauty of light on the world around them. They create these works either from visualizing the world around us, or reinventing it in their head. When an artist shares this with visual honesty and thoughtful expression in their medium of choice, it is a special form of communication between them and the viewer of the work. I believe art is one of the few ways of successfully sharing the sensation of a powerful emotion between two people, sometimes over the span of centuries. But this requires time and a situation where the artist will feel moved by their subject.

To return to confirmation bias, Penn and Teller are magicians and entertainers. Part of their shtick is that everything in magic is smoke and mirrors. Their movie, Tim’s Vermeer, is an attempt to prove that Vermeer’s art was also just smoke and (literally) mirrors. Tim Jenison is also operating under an almost pathological confirmation bias. In the movie he claims that when he looks at a Vermeer he sees it as a still from a video camera. I disagree, and using my own confirmation bias (combined with more evidence, experience, and using Occam’s razor) I would like to suggest that Vermeer had excellent training, spent a great deal of time learning to draw, and worked very hard over long periods of time to make his beautiful paintings. He painted in grisaille and glazed over it, perhaps repeatedly. But most importantly, he felt a strong emotional reaction toward the light falling on his subject, and I don’t believe that can happen looking at a subject upside down in a black box or reflected bit by bit in a mirror.

In art, the end does not justify the means. The means are an essential part of creating art in the first place.